As we begin to tell our story as Elders, we are finding that our journey takes us off on many “dirt roads.” Many of these paths are rock strewn dusty dead ends that we won’t bother relating. Some are quite thoughtfully scenic that we would like to share, but to do so we may need to clarify our language – so here is some terminology:

- Ancient Sunlight– used to denote petroleum, coal, natural gas, oil shale, tar sands, etc. – complex hydrocarbon molecules believed to have formed around 400 million years ago during the so called Carboniferous Period, when there was a large amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Over an estimated 70 million year period, sunlight stimulated the photosynthesis process that captured, sequestered much of this carbon and in this process patiently captured, converted and stored a significant fraction of the sun’s electromagnetic energy (light) incident daily on the planet in the form of biomass (plant life).

Because we currently perceive this one-time-only-supply of black stuff as an easy energy fix to burn in slave engines, we refer to it as “fossil fuel” – ignoring the fact that its usefulness far exceeds that of fuel. We ignore that the burning process returns the carbon to the atmosphere (in the form of carbon dioxide, etc.) where it resumes its role as a “greenhouse gas.”

To be perfectly clear, ANY use of Ancient Sunlight is unsustainable. If we humans were fully conscious, we would only use Ancient Sunlight so as not to have to use Ancient Sunlight. For example, using Ancient Sunlight to make a wind turbine that generates electrical power from wind energy might be a conscientious use of this one-time-only reserve- we are using Ancient Sunlight to harvest current sunlight.

An excellent easy to read reference on this topic is “The Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight,” by Thom Hartmann. - CAFO

- Cosmology

- Deep Time

- Emergence

[Ref: Chapter 30: Ecomorality: Toward Ethics of Sustainability, by Ursula Goodenough; from “A Pivotal Moment: Population, Justice & the Environmental Challenge,” edited by Laurie Mazer. ]

“Emergence: defined as the generation of something-more-from-nothing-but as a consequence of relationships.

Emergent properties arise in both non-life and life. A classic example in nonlife is the surface tension of liquid water. Surface tension is not a property of a single water molecule. It arises (“pops through”) as the consequence of water molecules in relationship with one another; water molecules(nothing-buts) generate surface tension (something-more) when they interact under particular conditions…

In life, the nothing-buts are cellular components—DNA, proteins, lipids, and so on—which are, in turn, nothing but atoms in relationship. Relationships between cellular components in turn generate the something-mores called biological traits, like motility, metabolism, photo-synthesis, vision, life cycles, and minds. Hence emergence is a layered concept: A something-more on one scale (the protein insulin, emergent from atoms) can serve as a nothing-but for a something-more at a different scale (the trait we call blood-glucose regulation).”

This term refers to the Phylogenetic tree of life – that acknowledges the common ancestry of all life on planet Earth – all animals, plants, etc. Thanks to our current understanding of DNA, all living entities appear to be linked to a common tree of life. Indeed all animals, plants, fungi, …. are distant cousins

[Ref: Right Relationship: Building a Whole Earth Economy”by Peter G. Brown and Geoffrey Garver ]

…”A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, resilience(stability), and beauty of the common wealth of [all] life. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” pg 5.

Another perspective of “right relations” is provided by Ursula Goodenough:

And now we are called to recognize our deep affiliation with, as well as dependence on, all the creatures and habitats of the planet. This realization has been translated as an invocation to be stewards, to take responsibility for reversing the many alarming trajectories the planet is taking. But “stewardship” puts us back into the mind frame of humans-as-other, hence I better resonate with the invocation that we be participants in establishing right relations with our fellow beings and our earthly habitat.

[Ref: Chapter 30: Ecomorality: Toward Ethics of Sustainability, by Ursula Goodenough; from “A Pivotal Moment: Population, Justice & the Environmental Challenge,” edited by Laurie Mazer. ]

There are many versions of the “The Universe Story” – a story that has blossomed beautifully in the past 50 years thanks to the increased awareness we now possess as a result of space exploration (e.g. Hubble Space Telescope, search for life on other planets, etc.), geologic and archaeological endeavours, and DNA research to mention a few. Modern thinkers, writers, and story tellers today include Thomas Berry, Brian Swimme,….. and many others. Among our favorites is college professor, biologist, poet and story teller, Ursula Goodenough who has recently written a Chapter of a larger book.

[Ref: Chapter 30: Ecomorality: Toward Ethics of Sustainability, by Ursula Goodenough; from “A Pivotal Moment: Population, Justice & the Environmental Challenge,” edited by Laurie Mazer. ]

We have included excerpts from this recent work of Goodenough (also available for review online) that she calls “The History of Nature.”

“It has been called various names: the Universe Story, the New Story, the Epic of Evolution. Here we can call it the History of Nature.

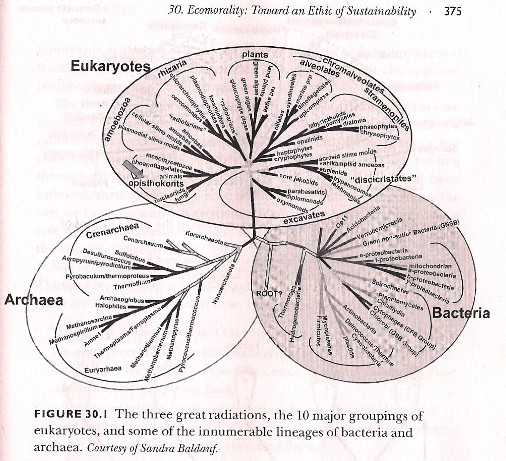

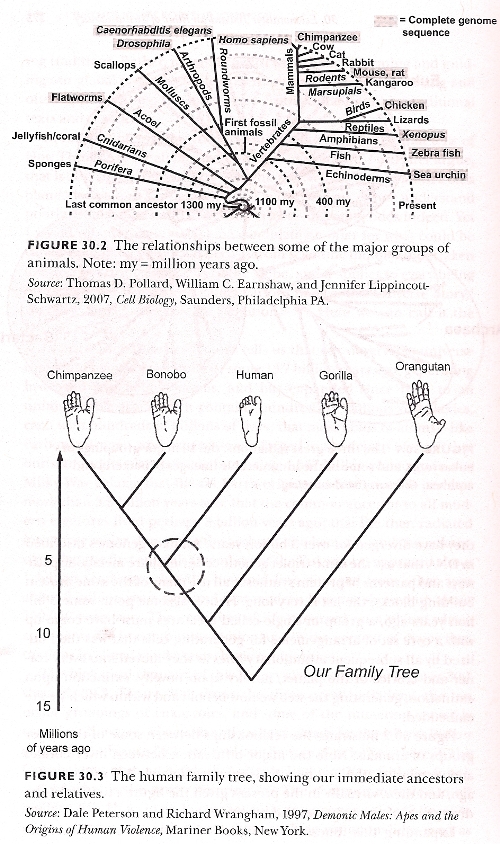

In brief, the History of Nature tells us that our observable universe came into being as a singularity some 13.7 billion years ago, generating hydrogen and helium atoms, and has expanded since then to an unimaginable size; that it contains hundreds of billions of galaxies, each with hundreds of billions of stars; that most kinds of atoms – like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen—-were forged in the depths of stars; that our star and its planets came into being 4.567 billion years ago in our Milky Way galaxy; that life on Earth originated from nonlife perhaps more than 3.5 billion years ago; that the common ancestor to all modern creatures lived perhaps 3 billion years ago; that life then radiated into three major domains—the archaea, the bacteria, and the eukaryotes; that the first animals (members of the Eukaryota) appeared about 1 billion years ago; that the hominid line diverged from other apes about 6 million years ago; and that modern humans showed up about 150,000 years ago. The evolution of life occurred on a planet whose continents are in continuous motion and in the context of major fluctuations in climate and atmospheric composition.

Because all the creatures on this planet share striking commonalities even as they diverged for over 3 billion years: All have genomes inscribed in DNA that use the same triplet genetic code; all share metabolic pathways and patterns of protein synthesis; all use many of the same protein building blocks; the list is very long. Hence, at some point some 3 billion years ago, a group of single-celled creatures must have come up with a core set of arrangements for generating cells that was then utilized by all subsequent evolutionary lines as they moved into every corner and crevice of the planet, novelty upon novelty, extinction upon extinction, generating the web we now behold and within which we are embedded…..

And at some point along the way, something else popped through: our narrative selves, the “I” that wakes up in the morning and falls asleep at night and has a rich autobiography. While it may be the case that other animals have versions of such selves, they clearly are front and center in human versions of consciousness. So here we are, new kids on the block, with traits that emerged from preexisting traits and yet seem so discontinuous, so unique, that most people still struggle to acknowledge our relationship to other apes, let alone to all the creatures shown in Figure 30.1.

I admit full-throatedly that I am thrilled and profoundly grateful to be a human. I am continuously astonished that I experience human-style awareness and can revel in the arts, the sciences, and the wisdom traditions transmitted via culture. Fully as thrilling, though, is the sense of my immersion in the totality of it all, generating a deep commitment to the proposition that this vibrancy continue. Which takes us to Which Things Matter

WHICH THINGS MATTER

How could the History of Nature begin to ground a common set of human insights on how best to move forward?

From my perspective, this is a no-brainer. Once the story is grasped and taken into one’s mind and heart, once one absorbs the iconic satellite images of Earth and experiences both its wonder and its fragility, there follows an outpouring of reverence and care, foundational components of a moral sensibility. Which things matter? The whole thing matters! When I give lectures to diverse groups and project [the graphics of the evolution of life] on the screen, there are two common responses: First, incredulity—“You mean we’re just that one twig?” and then, deep testimonials to affiliation—“I get it. We aren’t ‘other’ after all. We’re part of an enormous family.”

Goodenough then begins to summarize and introduces Right Relationship

And now we are called to recognize our deep affiliation with, as well as dependence on, all the creatures and habitats of the planet. This realization has been translated as an invocation to be stewards, to take responsibility for reversing the many alarming trajectories the planet is taking. But “stewardship” puts us back into the mind frame of humans-as-other, hence I better resonate with the invocation that we be participants in establishing right relations with our fellow beings and our earthly habitat.

Participation is at the core of the religious impulse. Those who share a story, share a common understanding of How Things Are, are moved to take part in its preservation, its continuation, and yes, its flourishing. They are motivated to put aside their own interests in the name of sustaining something that is much larger. A word widely used in religious contexts is faith. Faith has everything to do with the conviction that one’s story is true and that one’s moral tenets are sound.

Goodenough concludes with a suggested and hoped for path for the future of the planet:

At such time that the History of Nature becomes known, and celebrated, as the core of every body’s faith, then ecomorality, and its attendant commitment to achieve sustainability, will emerge as a guiding planetary principle.