Growing up back in the 1950’s, I didn’t get hooked by the dinosaur craze that gripped my brothers; it was enough to watch the Flintstones and their pet Dino sell cereal, vitamins, and whatever else wanted to sponsor their television show.

I was just glad that my brothers stayed out of my stuff while they were staging fights with plastic replicas of creatures whose names were the biggest words they could pronounce. The aggressiveness of those ugly beasties seemed to connect with something in the male DNA that left us girls clueless.

So why, these many years later, can’t I resist the impulse to get Milt to drive us six hours across Colorado all the way to the Utah border and the Dinosaur National Monument?

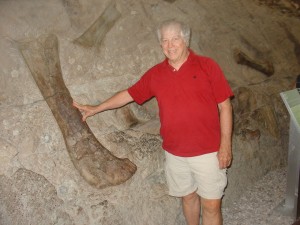

Our mutual fascination with Deep Time is rewarded with a view of the bone studded rock face that’s enclosed within the visitor’s center: we can touch the 147 million year old remains and marvel at how much the vertebrae, femur, and skull bones of four species of dinosaurs resemble our own skeleton.

Entranced, we promise ourselves an early morning pilgrimage out to a trail where 23 layers of Earth time reveal a narrative in which we the people occupy one/one thousandth of the amount of time on the planet that the dinosaurs did.

But meanwhile, during an overnight stay in nearby Vernal, we get to read up on the history of the historic site: how the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie instructed ‘his’ paleontologist to ‘find something really big’ for his museum in Pittsburg. The reptile layer of his own brain needed to best the competition during an earlier dinosaur collecting frenzy that was cut throat.

That same mindset is on display today, in the surrounding area: rich in shale oil and natural gas reserves, corporations are extracting the treasures of the commons and creating the conditions for a massive extinction caused by climate change.

Yet I have recently read another dinosaur story, one that reflects the bonding mammalian layer of our brain. Is it just a co-incidence that it involves a little girl?

India Wood was barely thirteen that first summer that her mother dropped her off at a friend’s ranch in the middle of nowhere (north west) Colorado. Because horses somehow fascinate young girls, she was probably thrilled that she got to ride through the arid countryside, exercising her imagination.

When she saw the large bone sticking out of a rock did she have any idea what she was looking at? Perhaps not right away, but she followed her curiosity to the local library and looked it up. Over the next three summers, she taught herself enough paleontology to painstakingly excavate almost half of an Allosaurus, a huge meat-eating dinosaur.

She carried the bones home to Colorado Springs, and stashed them in boxes beneath her pink spread covered bed.

When her mother worried that she needed the space for other teenage girl memorabilia, India offered her dinosaur to the Denver Museum of Nature and History. They hired her to lead the staff paleontologists back to the gathering site.

Together, they collected the rest of the skeleton that now graces the museum’s dinosaur exhibit. Young children, boys and girls alike, stand beside it in wonder and wondering.

And I now have a green plastic replica of her Allosaurus, to remind me that the India Woods of the world can transcend our reptile and even our mammalian brain layers, and live from the newest area of evolutionary mind, that place where Earth’s cumulative consciousness has become human conscience.

No Comments